Intro to Python

- On Linux systems I normally use the built-in Python (I only install anaconda for jupyter notebook functions. And I don’t run the init script which updates your .bashrc to activate anaconda when you open a terminal. Instead I activate manually with

source <PATH_TO_CONDA>/bin/activatewhen I want to use it and useconda deactivateto go back to std env) - For Windows I use Anaconda for python/jupyter notebooks. The Anaconda Navigator has a gui with options to create environments and install python packages. (I allow it to add to the PATH)

- For Windows/wsl be sure to run a

sudo apt-get updateandsudo apt install python3-pipto make sure you have all the Python tools installed.

A powerful aspect of python are all the additional packages you can install. Almost all projects you work on will likely require installing additional python packages (using pip). A nuance of this is that the package installed is specific to the python3 version you used to install it and there are frequently newer versions of Python3 coming out. Which means you end up managing packages for multiple python3 versions. Although extra steps it is cleanest to use virtual environments and always specifying the python version you’re using when executing scripts installing packages with pip ((venv)$ python3.7 -m pip install packageA vs generic (venv)$ python3 -m pip install packageA). If you use a venv for each project it will have its own python3/pip environment and will minimize the number of times you get confused or get missing module errors. ie you know you’ve installed a package before but don’t realize it was installed with a different version of python3. Especially if you install anaconda’s python3 distribution later on. Unfortunately I did not learn this til later so a lot of my references to python3 commands do not specify the python3 version.

Another Python version you will see is Jupyter notebook (which uses IPython as a backend. IPython is a dependency of Jupyter). Jupyter is a interactive Python interface usually using a web front end.

ipykernel package provides the IPython kernel for Jupyter. But you can manually create a venv and install it for usage in Jupyter. See below in venv notes.

For VS code to work with Python in Jupyter Notebooks you need to activate an Anaconda environment in VS Code or another Python venv in which the Jupyter package has been installed. If you don’t want to use Anaconda then

(.venv) python3.10 -m pip install jupyterwill install the Jupyter system, including the notebook, qtconsole, and the IPython kernel. You select the kernel in the upper right.

To check Python versions installed on your system.

$ ll /usr/bin/python3*

$ python3 --version (to see which version is used with generic python3 command)

(or just python* if you want to see python 2)

$ which python3.7 (will give you the path to python 3.7 binary/executable)

Advice on stackexchange..

Do not use “sudo” with pip install

ie do not use sudo pip install package

Instead run pip as a module with the -m using the specific python version you want

(venv) python3.7 -m pip install package

Inside the venv you can list locations (sys.path) Python is looking for modules to confirm the path of the module is included. There are both system (standard Python library) and site packages.

Standard Python library (.venv)$ python3.7 -c "import os; print (os.sys.path)" | tr "," "\n"

Show where third party packages, using pip, will be installed

$ python3.7 -c "import site; print (site.getsitepackages())" | tr "," "\n"

You can use pydoc to browse the locations in a browser and searches for the specific methods you’re using

$ python3.7 -m pydoc -b

If working in an editor like vs code you’ll need to make sure you have the right version of python3 selected (in vscode it can be selected in bottom right frame).

OOP vs Procedural

There are a couple different approaches to the over-all flow or framework of your code, how it is structured and organized. Procedural vs Object Oriented Programming (OOP).

Procedural is a fairly simple concept. Your code is written as a sequence of steps that are executed step-by-step. This makes sense when your project only requires a small number of steps to do some basic actions. You can still use functions, subroutines, procedures to organize actions that are often repeated to help keep the code clean and efficient. For quick, simple instructions procedural will be the most straight forward solution. But is it not as easy to scale up or build upon. If you plan on building on the project and making it a larger application then structuring your code with OOP will usually be better. (Almost all languages can do some level of procedural but the reverse is not necessarily true. There are some languages that are primarily procedural and could not do OOP. ie Fortran, C, and Basic)

In Object Oriented Programming (OOP) you try and think of your project in terms of objects. Each object usually contains data (attributes) and procedures (methods) that can access or manipulate the data. A method is similar to a function but resides inside the object. A common term you’ll here is class or the blueprint for your objects. (objects are instances of classes). My first interpretation of objects was that they are similar to complex variables that have both containers and functions built into them.

Since STEM projects will frequently use external Python packages objects (that are using OOP) early on you will run into OOP methods. Or you’re likely already using OOP concepts by using the built-in methods on python objects. For example using the .lower or .upper on a string. (You’ll notice it from the dot notation) Dot notation means you are accessing data or running an operation connected to that object. (ie using an external library to get the temperature might call something like sensor.temperature). So OOP allows you to create your own objects and better organize your code with larger projects. It also makes it easier for someone else to use your code.

import adafruit_dht

mySensor = adafruit_dht.DHT22(board.D18) # connected to gpio pin 18

temp = mySensor.temperature

Code example above using a DHT22 sensor and the adafruit dht library to get the temp data from the sensor.

- At the top of the code you import the adafruit DHT library (and the library is using OOP approach).

- You create a specific object representing your temp sensor (and it’s using a class in the adafruit library as the blueprint)

- Then you call on the temperature method of that object to get the temperature at which point you can put it in your temp variable.

So understanding OOP early on will make it easier to navigate using 3rd party packages along with allowing you to better structure your code for more complex projects.

It is also helpful to understand Python as modular programming. Python supports grouping these classes into separate files or modules. But you can easily import the module (step 1 above) to use in your own code. This helps with organization and allowing you to easily use code from other libraries. The modules are namespaced (ensures unique names) to avoid conflict when a class has the same name as a class in another module.

note - variables/functions usually use lower case for the names since class will use CamelStyle naming.

OOP Concepts

Two main components of OOP are classes and objects. (sometimes can be interchanged)

- Classes - this is the blueprint or template that defines the data(attributes) and available methods for acting on that data. (a complex user-defined data type). It lets you create your own user defined object.

- Objects - these are the specific instances of the class

Python Structure with OOP

- MODULE (module_name.py) is a python file that contains classes/functions and will have a .(dot) extension and can be executed/imported. If using OOP it will contain objects that are used to define the data and functions to work with that data.

- CLASS (ClassExample) is a type or container a variable can take on; just like int, float, str, list, dict. Typically uses CamelStyle naming.

- ATTRIBUTES - variables inside a class that define the data

- METHODS (class_method) - similar to attributes but define functions instead of data. Typically used to take some kind of action

- CLASS (ClassExample) is a type or container a variable can take on; just like int, float, str, list, dict. Typically uses CamelStyle naming.

Inheritance is the concept of building an object (child) or class based upon another (parent). The child inherits the attributes/methods of the parent class which reduces redundancy while also maintaining hierarchy. The child can add new attributes/methods that wouldn’t be applicable to the parent.

Two styles of OOP or inheritance models are

- class based inheritance (ie Python)

- prototype based inheritance (ie JavaScript). This can be confusing since JavaScript can use the ‘class’ keyword (considered syntactic sugar) to mimic a class type language.

JavaScript Structure with OOP

In JavaScript instances can be instantiated via constructor functions with the ‘new’ keyword.

Classes have to be specified in specific order. js can not use the class until it is defined in the code.

Encapsulation - the bundling of data and the methods that act on that data in objects. Access to that data from outside can be restricted. Wrap all properties into one object.

Constructor is a special method on js class. When called later using the new keyword, constructor will create one new blank js object and assign it properties and values based on the blueprint inside. It will run once when we instantiate the class using the new keyword.

Objects in js are reference data types which means that unlike primitive data types they are dynamic.

Inheritance - Extend the same behaviors. If property/method is not found in child it will look in parent

Abstraction - hide the implementation that is critical or does not need to be exposed. Avoids bugs.

Polymorphism - behavior of the object may change according to state or context.

Instantiation - create the object. return the handler.

Initialization (constructor) - set the initial/default values.

Other helpful terms to know

- Dynamically typed - you do not have to specify the data type (float, int, string) when writing the code. More convenient, common with scripting languages. The type is checked at run time when being executed. (Python/JS).

- Statically typed - you must specify the data type (float, int, string) of your variables to avoid errors during compile. Less convenient but can help catch bugs early on. (C++, Java)

- Strongly typed language means it will give an error if you try and perform an operation with incompatible data types (ie try and add an integer 1 and a string ‘2’. 1 + ‘2’ will give an error). The program will not make implicit conversions between unrelated data types for you. (Python)

- Loosely/weakly typed language will make conversions between unrelated data types. It will try and perform the action even if the data types are not compatible. 1 + ‘2’ = 3. (Javascript)

Helpful Python Commands

I will not be listing the Python syntax for loops, variables, conditionals, etc. There are many online resources for syntax including w3schools and udemy courses (I liked complete python bootcamp)

These are Python commands/concepts that I’ve come across and found useful.

Dictionary vs list

- dict - objects referenced by key names. Easy to reference an item by its name. But can not be sorted.

- list - objects referenced by location (similary to arrays). Can be sorted, indexed or sliced.

New Python versions will come out with features you may want to use. To install a new version on Linux (example below to install python3.7)

$ sudo add-apt-repository ppa:deadsnakes/ppa

$ sudo apt install python3.7

Can now run $ python3.7 or $ pip3.7

Next update venv to match the python version $ sudo apt install python3.7-venv

Now virtual environment can be created with $ python3.7 -m venv .venv

To add python3.7 to VScode. After installing a new version, closing, re-opening VScode recognized the new python as an option. Otherwise

$ which python3.7 (will give you the path to python 3.7 binary/executable)

Copy the path (ie. /usr/bin/python3.7)

In VScode change interpreter in bottom left and select “enter Interpreter path..”

Paste the /usr/bin/python3.7

Trying to change the default version of python3 was a hassle. It broke my gnome terminal. So I just type python3.7 or python3.8 (or which ever version using at the time)

Using pip

Advice on stackexchange..

Never use “sudo” with pip install

Do not use $ pip install package

Instead run pip as a module with the -m using the specific python version you want

$ python3.7 -m pip install package

Python-pip

Python pip Pip is the Python package manager. Many projects involve pip to install specific Python packages, ie the files needed for a module. Modules are python libraries that other people wrote which you can use in your code. This saves time/effort compared to trying to write all of the code from scratch. Pip packages can be found at pypi

Using pip

Note it is recommended to install packages inside a virtual environment to avoid broken/conflicting packages.

(.venv)$ python3.7 -m pip install package or

curl -sS https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py | python3.10

To see what packages are installed and the version

(.venv)$ pip3 list

Side note list vs freeze (.venv)$ pip3 freeze > requirements.txt

will list packages you installed in a txt file and in a format that can be used to reinstall.

To see the version of a package when not inside a venv

python3.7 -m pip show package

Upgrade pip python3 -m pip install --upgrade pip

or curl -sS https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py | python3.10

pipx is a tool similar to brew, npx, apt. It is designed for isolating application installation.

python3 -m pip install --user pipx

```pipx install virtualenv``

Python wheels Often during a pip installation you’ll see reference to wheels. Python wheels are a tool that help install python packages. From stack overflow.. if the package is not a wheel, pip tries to build a wheel for it (via setup.py bdist_wheel). If that fails you get “failed building wheel for package” and pip falls back to installing directly (via setup.py install). Once we have a wheel, pip can install the wheel by unpacking it correctly. pip tries to install packages via wheels as often as it can. This is because of various advantages of using wheels (like faster installs, cache-able, not executing code again etc).

If having problems with wheels you can try installing/updating.

$ python3.7 -m pip install --upgrade pip setuptools wheel

or

$ pip install <package> --no-cache-dir

There are times I’ve had problems getting the pip version of a package to install and had to use apt.

ie pip3 would not work for RPi.GPIO on a project so I used apt

$ sudo apt install python3-wheel

$ sudo apt-get install RPi.GPIO

Python-venv

Using a virtual environment involves a couple extra steps but is a good practice. In my projects I only use python3 and venv for simplicity. (vs virtualenv or pipenv). The concept is that you’re creating an isolated, unique python environment/folder which can be activated when working on a specific project. That environment will have its own Python and when you install python packages they will be specific to that environment. This helps handle the scenario where different projects have the same dependency; or share the same packages but different versions of that shared package which creates a dependency conflict. venv handles the conflict by isolating the project dependencies and allowing you to install a specific version of a package within that project folder; without affecting other projects. Since you start with a clean slate each time you can also use commands to see what packages are necessary for your project (and version), output them to a requirements.txt file and use it to easily install on another system.

Note - if you want to run your python program outside the venv (during startup of RPi) then you need to put the location of the venv python being used in the shebang !# header of your python program.

For example

#!/home/pi/projectA/.venv/bin/python3

You can then make it executable with

$ chmod +x filename.py

Now you can execute it with

$ ./filename.py

To see more details go to shebang section

Installation (may need to go through update/upgrade steps)

$ sudo apt install python3

$ sudo apt install python3-pip

$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt upgrade

$ sudo apt install python3-venv

Often you’ll be using a different version of python from the python3 default on your system (ie 3.8, 3.9) just replace python3 with python3.7 or python3.8 etc.

Quick steps

Install virtualenv

python3.7 -m pip install virtualenv create a new project folder and activate the venv

$ mkdir project-name && cd project-name

$ python3 -m venv .venv

You can change the second .venv to whatever virtual env name you want. The .venv folder will contain python and packages you install.

Now use ‘source’, a built-in shell command to read/execute the contents of the ‘activate’ file

$ source .venv/bin/activate (a .venv will now be at the beginning of your command prompt line)

In VS code select the Python interpreter created in the venv from the menu at the bottom right of the window. Or go to command palette, ctrl-shift-P, and then type ‘Python: Select Interpreter’ and choose your venv.

Jupyter Notebook in venv I usually using anaconda for jupyter notebook so instructions are for venv inside conda. conda create -n .venv python=3.10 conda activate .venv pip install --user ipykernel python -m ipykernel install --user --name.venv # manually add the vevn kernel Now you can go to Jupyter Notebook and refresh and you should see .venv as an option when creating a new kernel. You can also switch once inside the notebook. jupyter kernelspec uninstall .venv to remove the kernel

git Housekeeping Item Add .venv to your .gitignore list so you do not load it to github. This can be done automatically when you create the repo by selecting Python template for your git ignore.

To turn off the venv

(.venv)$ deactivate (when you’re done and need to deactivate.)

To remove the venv just delete the venv folder with recursive/force flags

$ rm -rf .venv/

Move/Install project in another location

(.venv)$ pip3 freeze(or $pip3 list -v or $python3 -m pip list -v) to see what packages are installed

(.venv)$ pip3 freeze > requirements.txtto output in a file for installing in another location

or $ python3 -m pip3 freeze > requirements.txt

Go to new location and create/activate a .venv

$ python3 -m venv .venv

$ source .venv/bin/activate

install with -r for requirement install

(.venv)$pip3 install -r requirements.txt

or $ python3 -m pip install -r requirements.txt

May have to remove pkg-resources from the requirements.txt to avoid errors when installing on another system.

Installing/uninstalling packages

(.venv)$ python3 -m pip install package-name

Can use find to see where it was installed

(.venv)$ find . -print | grep -i package-name

(do not need to use * wildcards, will find files and folders)

To uninstall

(.venv)$ python3 -m pip uninstall package-name To upgrade a package

(.venv)$ python3 -m pip3 install --upgrade <package>

To remove a .venv rm -r .venv

Other Commands

Install requests (useful for making HTTP requests in Python)

$ python3 -m pip install requests

Install from source

$ cd <source name>

$ python3 -m pip3 install .

To get access to site packages go into the virtual env folder and edit pyvenv.cfg

change include-system-site-packages=true

Module installations will still go to venv as normal and site packages will be visible too.

Troubleshooting

Helpful commands when you get ‘module not found’. Make sure the python version you’re using has the module installed and the pip version is upgraded too. If you believe you’ve already installed the module before it’s possible you installed it in an earlier version of Python. If using vs studio or other IDE check which Python version it is using.

Inside the venv list locations (sys.path) Python is looking for modules to confirm the path of the module is included.

(.venv)$ python3 -c "import os; print (os.sys.path)" | tr "," "\n"

You can use pydoc to browse the locations

$ python3 -m pydoc -b

Some folder explanations

- bin - the executables you use in the venv. ie activate

- include - used for compiling the python packages.

- lib - where the python version you’re using for the venv is stored/installed and site package folder for dependencies.

Example

├── bin

│ ├── activate

│ ├── pip

│ ├── pip3.6

│ ├── pylint

├── include

├── lib

└── python3.6

Python Framework

Python Infrastructure

BOTTOM

- MODULE (module_name.py) is a python file that contains classes/functions and will have a .py extension and can be executed/imported.

- PACKAGE (package) is a directory with a collection of modules and will include __init__.py (constructor) so the interpreter knows it is a package.

- LIBRARY is a collection of packages. More of a generic term meaning a collection of code that is designed to be re-used. A library can be a collection of packages/modules or even a single module.

- FRAMEWORK is a collection of libraries.

- (API or application programming interface is an interface or description of how to interact with an application)

TOP

Example

The files inside of a package temp-measure might be

/temp-measure/

__init__.py

ntc_measure.py (module)

dht11_measure.py (module)

To use a part of the module, import it, create an object, and then access the data or methods.

import ntc_measure.py

sensorA = ntc_measure.sensorSetup(pin 18)

temp = sensorA.readtemp()

- MODULE (module_name.py) is a python file that contains classes/functions and will have a .py extension and can be executed/imported. OOP will involve objects where you combine data (attributes) and functions (methods/actions) to work with that data.

- CLASS (ClassExample) is a type or container a variable can take on; just like int, float, str, list, dict. Typically uses CamelStyle naming.

- OBJECT is a specific instance of a class.

- __init__() method is a constructor. Creates INSTANCE variables instead of CLASS variables. Initializes an object within a class. This helps avoid the issues of class attributes that are mutable (like a list) and being modified by other objects unintentionally.

- ATTRIBUTES are variables inside a class that define the data (variable_name, CONSTANT_NAME)

- METHODS (class_method) are similar to attributes but define functions instead of data. Typically used to take some kind of action.

When using a third party package (ie a package you installed with pip) it is sometimes helpful to go look at the modules to see what they’re doing and what arguments can be passed.

For example

speedtest-cli is a python package that can be used to get your network download/upload speed.

- You can either use the command line or call the modules in your python code. For the cli to work I was having to use the –secure flag (otherwise I got an HTTP error).

- However it was not clear how to use the ‘secure’ option in python code. But if you went to the speedtest.py module (in a venv it was under venv/lib/python3x/site-packages) and looked at the arguments in the Speedtest class you could see there was a secure=False flag. Passing secure=True allowed Speedtest to run in the code.

class Speedtest(object): """Class for performing standard speedtest.net testing operations""" def __init__(self, config=None, source_address=None, timeout=10, secure=False, shutdown_event=None): - Another method to browse the Speedtest class arguments is using pydoc. Go into the directory and active the venv and then run

$ python3 -m pydoc -b

It will open a browser where you can go to the site-packages and looks at the speedtest module/classes.

Some underscore naming conventions:

_(single): internal, weaker enforcement, can use to indicate the scope.

__(double): private, stronger enforcement, I don’t use my own version of these.

SINGLE(internal)

_var, _method, _attr : Indicates it is meant for private, internal use, and not to be imported. Has ‘weak’ enforcement. (ie Python will not import when ‘import *’ used)

var_ : Naming convention to make the variable different from a Python keyword

DOUBLE(private)

__method or __attribute : Not recommended. Makes the method/attribute private and can’t be accessed outside the class. ‘Stronger’ enforcement. Will cause naming mangling (ie will become Class._Class__method)

__method__or __attr__ : Indicates a special or magic Python method. Do not use for your own naming.

- self keyword is passed into methods to let python know that it’s not just a simple function but a method connected to that class. So ‘self’ connects methods to the class.

- default constructor will only have one argument, self, which is referencing the instance being constructed.

- parameterized constructor can have extra arguments you pass to it.

Helpful Troubleshooting Commands

Lists locations (sys.path) Python is looking for modules (can do inside venv)

$ python3 -c "import os; print (os.sys.path)" | tr "," "\n"

Show where third party packages, using pip, will be installed

$ python3 -c "import site; print (site.getsitepackages())" | tr "," "\n"

note - There are both system (standard Python library) and site packages. This command prints site packages.

-c command –> Specify the command to execute. This terminates the option list (following options are passed as arguments to the command).

-m module-name –> Searches sys.path for the named module and runs the corresponding .py file as a script. Examples in python -m section

dir() - List all properties and methods of an object.

globals() - Returns dict of variables defined in global symbol table (namepsace).

locals() - Returns dict of local symbol table

From the python interpreter - in a script use pprint(dir()) for pretty printer. (from pprint import pprint)

Can import modules and re-run dir() to see what was loaded.

>>> import modules

>>> dir()

>>> import moduleA

>>> dir()

Can create an object and run dir(myObject)

>>>exec(open("file.py").read())

>>>globals()

Or put it inside a function with pprint(globals())

Python -m flag

The python -m flag allows you to execute a python script (file.py) from the command line by using the module name (file) rather than the entire file name (path/to/file.py). When running a single file it will execute as “main” (so you can use name=”main”). This has little advantage when you’re running a python script from your directory.

$ python3 -m file

vs

$ python3 file.py

Small note -

python3 -m file –> sys.argv[0] = full/path/to/file.py

python3 file.py –> sys.argv[0] = file.py

The main -m advantage is running built-in python modules as one-liners. See examples below.

You can also use -m on one of your packages (folder). When running -m on a package

First evaluates the __init__.py (adds the “import” ability)

Any code in imported modules will be executed (not in the name=”main”)

Then runs the __main__.py file (__main__.py is required to run -m on a package).

So how does it work..

Example to create a simple web server at port 8000 from any directory

$ python3 -m http.server 8000

(can now go to http://IPaddress:8000 from any PC on your network)

The command executes server.py (module) in http folder (package)

Why does this work?

Python looks for modules in the current directory, paths from PYTHONPATH, and the installation-dependent defaults.

To see the defaults sys.path use

$ python3 -c "import os; print (os.sys.path)" | tr "," "\n"

This shows /usr/lib/python3.6 in my sys.path

http/server.py is under python3.6

/usr/lib/python3.6/

├── http

└── __init__.py

└── server.py

An even quicker way of seeing this is using the pydoc module

In the same directory run

$ python3 -m pydoc -b

A browser should open. Find http under python3.6 and you can navigate to server.py

Pydocs

go into a folder and run pydoc to create an HTTP server at the port specified with python documentation. Will show __doc__ files for your classes, functions.

$ python3 -m pydoc -p 8001

$ python3 -m pydoc -b (open browser using next available port)

Python pdb debugger (useful for debugging in a terminal on Pi0)

$python3 -m pdb file.py

Profilers and timers (cProfile, timeit, pstats)

$ python3 -m cProfile -o output.cprof file.py

>>> import pstats

>>> p = pstats.Stats('output.cprof')

>>> p.sort_stats('cumulative').print_stats(10)

Or view results in SnakeViz

$ snakeviz output.cprof

To install

$ sudo pip3 install pstats-view

$ sudo pip3 install snakeviz

Simple http.server Simple web server that allows you to browse folder/files and download a file. Can also serve static html files.

$ cd <directory>

$ python3 -m http.server 8000

You can now go to hostname.local:8000 from any PC on your network and see your folder/files.

pi@raspberrypi:$ python3 -m http.server 8000

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 8000 (http://0.0.0.0:8000/) ...

10.0.0.100 - - [14/Mar/2021 11:52:10] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

Package Module Importing

Python Package-Module Import Packages are directories with a collection of modules.

- Package directories will often contain a __init__.py (which indicates it is a package)

- When a package (or module in the package) is imported the __init__.py is executed.

- Code in the __init__.py can be used for package initialization.

A module is a python file (file.py) that contains classes/functions that can be used in other python scripts. It can be located in a package or stand alone.

- A module can be imported in a python script with

import module - Or executed as a script at the command line with

$ python3 module.py

The method for getting access to another module’s classes/functions is through “import”. When python sees the import package or module line it will look in the following locations for that directory/file.

- Current directory

- Directories listed in $PYTHONPATH (see PYTHONPATH section for details)

- The installation-dependent list of directories (specific to python version)

- Additional method is adding sys.path.append(/path/to/dir) in your code. The path will be added temporarily when your code runs.

To see a list of your python packages (directories) you can print(sys.path). A quick way of doing this at the command line using the -c flag.

$ python3 -c "import sys; print (sys.path)" | tr "," "\n"

/usr/lib/python3.6 (you’ll see standard python packages you’ve used)

$HOME/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages (you’ll see packages you’ve installed with pip)

/usr/lib/python3/dist-packages (you’ll see packages installed with apt)

If you look inside these directories you may see

- __init__.py (makes a directory a package and may list what modules will be loaded)

- directory (this could be a sub package)

- files.py (these are the modules containing the classes/functions)

Another way to find the location is in the interpreter. Import a module and print the __file__ variable. (however this does not work on built-in modules)

>>> import http

>>> http.__file__

/usr/lib/python3.6/http/__init__.py

Executing a module as a Script

When developing a module it is useful to execute the module as a script for testing and further development (unit testing). But when importing the module into another script you typically do not want it to execute that code.

An easy way to handle this is

- put an “if” condition in your module where you place your “unit testing” code

- and __name__ == ‘__main__’

__name__ is just a variable python assigns to the file being executed

When a module (or script) is executed as a script (ie $ python3 module.py)

- __name__ = ‘__main__’

When a module is imported in another script (ie import module)

- __name__= module name

So in your module put the if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

my_module.py

def myfunction():

print("this is where the function does stuff")

print(__name__)

if __name__ == '__main__':

print("this is where i test the function")

myfunction()

Now if you import this module in another script and call myfunction() it will only execute the myfunction. (because __name__ will = ‘my_module’)

But if you execute the module as a script. $ python3 my_module.py

It will run the code inside the “if” condition because __name__ will = __main__

Experimenting with the “import”

Early on your projects will be single python scripts or a single file (file.py). But even on these early scripts you’ll likely be leveraging off other python packages/modules and using “import”. There are two common methods for importing. (example below with a module)

Options

import module-

from module import function(or Class)

(note - most examples below use the function scenario. But you could also test by instantiating/creating an object with a = Class())

Option 1. You have imported the module into the local symbol table but its contents are still private. You have to use dot notation and call the objects specifically with module.func()

Option 2. You have imported the module objects directly so you directly call func(). The danger is if you already have a func() imported from a different module it would be over-written. You can avoid this by renaming using import ‘as’

from module import func as thisfunc

Now you use thisfunc()

Below goes thru an example with the built-in “time” module often used for creating a short delay/pause in your code. Since “time” is a built-in module it is easier to use pydoc to find it.

First run pydoc -b to show a list of python packages/modules

$ python3 -m pydoc -b

or

$ python3 -m pydoc -n 10.0.0.222 (any device on network can access)

>>> python3

# Option 1 above. Import time into the current namespace

>>> import time

>>> dir()

# Since we imported "time" we'll see it listed in dir(), the current local symbol table. And we know from pydoc that "sleep" was the function inside "time". So we use it with ..

>>> time.sleep(2)

# Option 2 above. Now directly import sleep

>>> from time import sleep

>>> dir()

# Can now see "sleep" listed. So call it directly ..

>>> sleep(2)

A browser window should open up with the python package/modules. You’ll recognize the same directories listed from sys.path above. However the built-in modules are included here, too.

Under Built-in Modules select “time”. Scrolls past the Classes down to the functions and you’ll find “sleep”. Now use the interpreter to experiment with importing it. Use pydoc to Explore Packages/Modules

Pydoc is a graphical way to explore packages/modules in a directory (packages/modules you’ve created in that directory and the installed packages/modules by python).

Create Your Own Package Module

The best way to get familiar with the package/module concept is creating your own packages (directories) and modules (file.py).

- Create __init__.py inside the directories to make them packages.

- Create simple functions with a print(“function”) inside the modules. Now experiment with different import syntax.

# User |- user-script.py # Developer ├── package │ ├── __init__.py │ ├── moduleA.py | | functionA() │ ├── moduleB.py | | functionB()

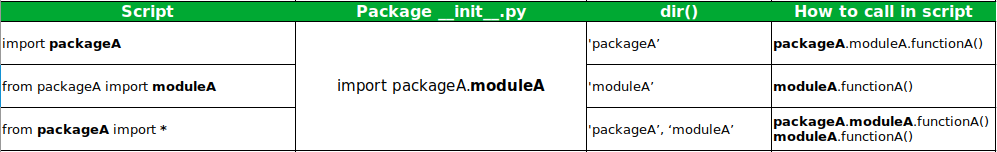

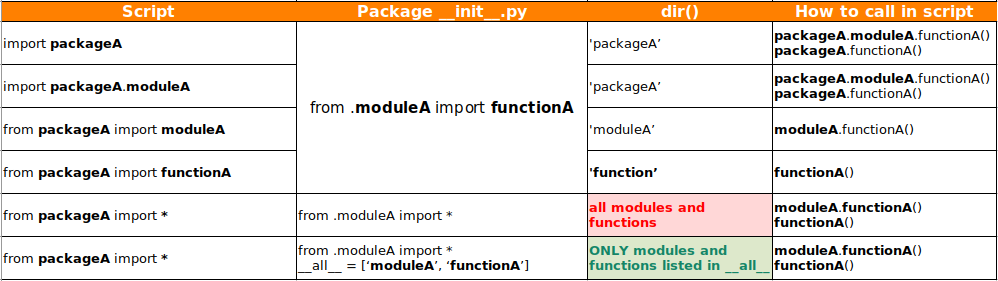

Do iterations of changing your package __init__.py and method of importing in the script.

Each time check dir() to see what is loaded into the global namespace. (you can also do dir(object))

For packages/modules that you build yourself it is easier to experiment with the import function using REPL and dir().

Create a package/module/function setup like above.

The function just does a simple print(“this is functionA”)

Test 1

package __init__.py = from .moduleA import functionA

$ python3

>>> import package

>>> dir()

Try and execute the test function

>>> package.module.functionA()

>>> package.functionA()

>>> functionA()

quit() and try another iteration to see how dir() changes. Note - if you don’t quit and keep importing thru different methods you’ll notice you can call a function with multiple conventions.

User and Developer Modes

Although you may often be both the user and developer it is useful to think in both modes. You want to develop your package/init.py so that later you can easily user the modules.

__init__ –> import package.module

From developer side can list which modules are visible from the package

Developer - 'specific'

package/__init__.py

import package.moduleA

# import package.moduleB

# Can control what modules/functions are visible

User can import all (*) modules or specific modules that were listed in the __init__.py.

User-script.py

from package import *

a = moduleA.functionA()

# can not call moduleB.functionB()

User can import package and call package.module.function

User-script.py

import package

call package.moduleA.functionA()

If the user knows the modules can import them specifically, regardless of the init.py

User-script.py - if user knows the module can still specifically import it (even if init.py does not)

import package.moduleB as mymod

call mymod.functionB()

from package import moduleB

call moduleB.functionB()

__init__ –> from module import *

From developer side can import all (*) classes/functions or be specific. This controls what is visible to the user.

The downside of the ‘all’ (*) is that the user can see all functions/classes (even when not intended to be used by the user)

The downside of the ‘specific’ scenario is that you have to keep updating your init.py as you add more functions.

Developer - 'all'

package/__init__.py

from .moduleA import *

from .moduleB import *

# All functions are available to the user to import

Developer - 'specific'

package/__init__.py

from .moduleA import functionA

from .moduleB import functionB

# Can control what functions are available to the user to import

Since classes/functions are imported in init.py the user can call package.function()

User-script.py

import package

#call package.functionA()

package.functionA()

#call package.functionB()

package.functionB()

Or the user can directly import the function

User-script.py

from package import functionA

call functionA()

__init__ –> from module import * (_all__ = [‘module’])

From developer side if you want to limit what is visible (what should be called by the user) then the __all__ can be defined to specify what the user sees with “import * “

Developer - 'specific'

package/__init__.py

from .module import *

__all__ = [

'moduleA',

'functionA'

]

# Can control what modules/functions are visible

User can import package modules that were listed in the init.py.

User-script.py

from package import *

call moduleA.functionA()

call functionA()

# can not call moduleB.functionB()

User can still call specific modules if the name is known.

User-script.py - if user knows the module can still specifically import it (even if init.py does not)

import package.moduleB as moduleB

call moduleB.functionB()

from package import moduleB

call moduleB.functionB()

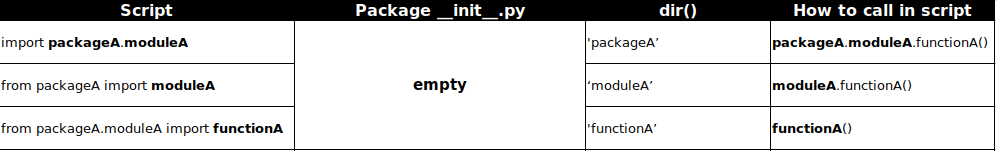

Regardless of the package init.py (or if it even exists) you can import directly if the module/function names are known.

uPython

MicroPython has a subset of Python libraries but there are some areas where the projects will deviate. Especially if you want to take advantage of more recent Python3.7+ features.

Other differences come up due to the packages that are used for one vs the other. A good example is mqtt.

mqtt

- For RaspberryPi/Python3 I use paho-mqtt - Paho does not require topics to be defined in binary format.

- For esp32/uPython I use umqtt.simple - umqtt.simple requires topics to be in binary (b’topic’) format. This is to save memory. MQTT requires binary format and converting back-and-forth between string-binary would be extra steps.

Another example is logging. logging

- Python3 has comprehensive built in logging modules.

- upython there is a basic version. To make it more advanced you have to add to it.

See section on logging

Get uPython System Info

esp32 CPU info

import machine

cpufreq = machine.freq()

To set the freq

machine.freq(240000000)

Python/RPi

f = open("/sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq")

cpufreq = int(f.read()) / 1000

When possible it is best to use integers in upython to keep the processing time as low as possible.

At 0.24MHz my esp32 showed

Integer calculations (+,-,//,) take 0.025ms

Float calculations (+,-,/,) take 0.03-0.04ms

100 calculations would add up to an extra 1ms in process time. This is significant with a stepper motor project where the delay needs to be <1ms.

Time.sleep (<1 sec delays)

Python sleep can be entered as a decimal

from time import sleep

sleep(0.001) # 1ms sleep

upython

Some boards do not support sleep as a float. Can use sleep_ms or sleep_us

from time import sleep_us

sleep_us(1000) # 1ms sleep .. enter an int in us

Timer Analysis

Python

perf_counter() includes delay times

process_time() derived from CPU counter so doesn’t update with delay

from time import perf_counter_ns # (the _ns is with 3.7+)

time_ns = perf_counter_ns() # returns integer, ns. Includes delay times

print("code that is being timed")

time_ns = perf_counter_ns() - self.time_ns

time_ms = time_ns/1000000

For python can also use timeit

uPython

import utime, uos

time_us = utime.ticks_us() # returns integer, us. Includes delay times

print("code that is being timed")

time_us = utime.ticks_diff(utime.ticks_us(), time_us)

time_ms = time_us/1000

Another solution for both python/upython is creating a Timer class with start/stop methods built-in. (python Timer can be installed from pypi)

logging

Logging can be used to debug code and/or trouble shooting system issues.

For system logging

- logs during boot

- systemd logs

- journalctl

- var/logs

Check out the system logging page.

For debugging

The logging library has many useful features compared to standard print statements. It is installed with standard python installation and does not require extra install.

- There are multiple levels of logging (see levels below). DEBUG and INFO are the levels I use the most. I keep status and general information print statements at the INFO level and more detailed print statements with variables at the DEBUG.

- You can easily toggle these logging/print statements on/off for the entire code by changing the level.

- This on/off toggle can also control the logging for modules that are imported. (You can either pass the logger to them or use a root logger)

- There are logging options to include both printing to the console and/or a log file.

- There is a journal option to output the logs to the PC systemd journal (useful when your python script is running as a systemd service).

A couple approaches

- basicConfig Quick, simple logging with basicConfig(). With basicConfig() you can configure the root logger. I’ve noticed many modules in other libraries will also use the root logger so you can control the log level for them from your main script, too.

- RotatingFileHandler More advanced options with RotatingFileHandler. When you want to output to multiple places (console/standard output stream, a log file, and the journal) it is better to use Handlers. RotatingFileHandler lets you specify the max size of the log and enables rolling log files. I have found both types of logging to be useful so I include an option for either in my main script. The template I use is below in the RotatingFileHandler example.

basicConfig()

How to use basicConfig() logging in a python script

There are 5 levels of logging listed from lowest to highest (DEBUG/INFO do not get output by default. So you specify the level=logging.DEBUG in your code to force them)

- DEBUG

- INFO

- WARNING

- ERROR

- CRITICAL (can use this to turn logging off essentially)

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG) # Can set to CRITICAL to turn it off

logging.debug('Output to console')

# or to log to a file using log format option

log_format = '%(asctime)s %(filename)s: %(message)s'

logging.basicConfig(filename='test.log', format=log_format, level=logging.DEBUG)

logging.warning('Send to log file')

'''Can use the logging.error and exc_info=True to include the stack trace in the log (lists the function ran up to the point of the exception thrown)'''

dummy_list = [1, 2]

try:

print(dummy_list[2])

except Exception as e:

logging.error("exception error", exc_info=True)

# Another method

try:

functionA()

except IOError as e:

logging.info(e)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

logging.info("ctrl c")

exit()

RotatingFileHandler()

How to use RotatingFileHandler() logging in a python script

For more logging options you can replace basicConfig() with RotatingFileHandler(). This allows you to create multiple handlers outputting to different levels of logging to multiple places (console or a log file). You can also specify the max size of the log file.

The 5 levels of logging are still used. Listed from lowest to highest (DEBUG/INFO do not get output by default. So you specify the level=logging.DEBUG in your code to force them)

Function below will create 3 handlers for three outputs (console, regular log, error log).

The auxillary loggers will only output up to the lowest level of main_logger.setLevel

If main_logger.setLevel is off (logging.CRITICAL) then the other loggers will not output.

def setup_logging(log_dir, log_level=logging.INFO, mode=1):

# Create loggers

if mode == 1:

logfile_log_level = logging.CRITICAL

elif mode == 2:

logfile_log_level = logging.DEBUG

main_logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

main_logger.setLevel(log_level)

log_file_format = logging.Formatter("[%(levelname)s] - %(asctime)s - %(name)s - : %(message)s in %(pathname)s:%(lineno)d")

log_console_format = logging.Formatter("[%(levelname)s]: %(message)s")

console_handler = logging.StreamHandler()

console_handler.setLevel(logging.CRITICAL)

console_handler.setFormatter(log_console_format)

exp_file_handler = RotatingFileHandler('{}/debug.log'.format(log_dir), maxBytes=10**6, backupCount=5) # 1MB file

exp_file_handler.setLevel(logfile_log_level)

exp_file_handler.setFormatter(log_file_format)

exp_errors_file_handler = RotatingFileHandler('{}/error.log'.format(log_dir), maxBytes=10**6, backupCount=5)

exp_errors_file_handler.setLevel(logging.WARNING)

exp_errors_file_handler.setFormatter(log_file_format)

main_logger.addHandler(console_handler)

main_logger.addHandler(exp_file_handler)

main_logger.addHandler(exp_errors_file_handler)

return main_logger

# Set next 3 variables for different logging options

logger_log_level= logging.DEBUG # CRITICAL=logging off. DEBUG=get variables. INFO=status messages.

logger_setup = 1 # 0 for basicConfig, 1 for custom logger with RotatingFileHandler (RFH)

RFHmode = 2 # If logger_setup ==1 (RotatingFileHandler) then access to modes below

#Arguments

#log_level, RFHmode| logger.x() | output

#------------------|-------------|-----------

# INFO, 1 | info | print only

# INFO, 2 | info | print+logfile

# DEBUG,1 | info+debug | print only

# DEBUG,2 | info+debug | print+logfile

if logger_setup == 0: # Use basicConfig logger

if len(logging.getLogger().handlers) == 0: # Root logger does not already exist, will create it

logging.basicConfig(level=logger_log_level) # Create Root logger

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) # Set logger to root logging

logger.setLevel(logger_log_level)

else:

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) # Root logger already exists so just linking logger to it

logger.setLevel(logger_log_level)

elif logger_setup == 1: # Using custom logger with RotatingFileHandler

logger = setup_logging(path.dirname(path.abspath(__file__)), logger_log_level, RFHmode ) # dir for creating logfile

logger.info(logger)

logger.debug('this will only print when level set to DEBUG')

# Can pass the logger and log_level to sub modules

example_function(mlogger=logger, mlog_level=logger_log_level)

MicroPython Logging (ulogging)

Logging statements with string formatting will add a small amount of time to the code even when the logging level is set higher. On the esp32 (.24MHz) each logging statement added 10ms. When I’m finished with debugging I comment or remove the logging statements for esp32 projects.

The basic upython version of logging is on github

It follows similar syntax

import ulogging

'''

CRITICAL = 50

ERROR = 40

WARNING = 30

INFO = 20

DEBUG = 10

NOTSET = 0

'''

a = "test"

ulogging.basicConfig(level=10)

ulogging.info('root logger info: {0}'.format(a))

ulogging.debug('root logger debugging')

logger = ulogging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.setLevel(10)

logger.info('logger info: {0}'.format(a))

logger.debug('logger debug')

Cheat sheet

Data types

- int

- float

- str

- list (ordered sequence of objects)

- C++ std::vector

- JavaScript: Array

- Ruby: Array approximated

- HTML: can use js array

- PHP: array[], key is optional

- dict (unordered key:value pairs)

- C++ no built-in dict type

- C# Dictionary

- JavaScript: Object

- Ruby: Hash

- Java: Map approximated

- PHP: array[]

Lists and Dictionaries

dictA = {} # initialized empty

dictA['car'] = 'ford'

listA = [] # initialized empty

listA.append('red') # since started empty need to use .append to assign a value

# also .append would be required to keep adding more items to the list

# But can change the value assignment with []

listA[0]='blue'

# Can also initialize multiple items in a list during declaration

channels = 4

list = [0]*channels

2D list

list2D = [[]] # first list is initialized with a 2nd list

# note 2nd list is empty and would require .append to assign a value

# or

list2D = [[0]] # both lists are initialized with objects and can be assigned using []

list2D[0][0]=1 # [[1]]

list2D.append([2,3]) # [[1], [2, 3]]

list2D[0] = [0,1] # [[0, 1]]

list2D.append([2,3]) # [[0, 1], [2, 3]]

list2D[0][1] = 4 # [[0, 4], [2, 3]]

Check if an item exists in a list

if x in listx:

Iterate through items in a list

listx = [0]*5

for x in listx:

print(x)

List comprehension + logic

tempC = [0, 20, 40, 80]

tempF = [(9/5*temp+32) for temp in tempC] # [32.0, 68.0, 104.0, 176.0]

oddeven = ['EVEN' if x%2==0 else 'ODD' for x in range(0,11)] # ['EVEN', 'ODD', 'EVEN',..]

Dictionary and avoiding/handling errors

dict = {}

dict['a'] = 'alligator'

dict['b'] = 'boxer'

dict['c'] = 'cat'

print(dict) # {'a': 'alligator', 'b': 'boxer', 'c': 'cat'}

print(dict['a']) # Simple lookup, returns 'alligator'

dict['a'] = 6 # Put new key/value into dict

'a' in dict # True

## print(dict['z']) # Will throw a KeyError

if 'z' in dict: print(dict['z']) # Avoids KeyError

print(dict.get('z')) # Prints 'None' instead of throwing a KeyError

Check for a specific key or value in a dict

testdict = {'akey':123}

123 in testdict.values()

'akey' in testdict.keys()

Check if key exists in a dictionary

if dict.get(key) == None:

Check if dict is empty

bool(dict)

list() function will create a list object.

str='hello'

list(str) = ['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']

dict = {'alpha': 1, 'beta': 2, 'gamma': 3, 'delta':4}

list(dict) = ['alpha', 'beta', 'gamma', 'delta'] # <-return the keys as a list

*dict = alpha beta gamma delta # <- will unpack the keys

: is arrange. If now lower, upper then will select all [:] Python includes the lower bound but excludes the upper bound. So [:-1] starts at 0 but does not includes the last. to select first 2 row/col use [0:2, 0:2] to select last 2 row/col use [-2:, -2:]

Functions and Arguments

Functions can return a value or return nothing (void function). A function that is meant to perform an action could be called a procedure. Passing variable number of arguments in a function. Terminology changes when referring to definition vs call of the function. Order is positional/non-default then keyword/default(a=1)

Defining the function

4 positional arguments. a,b are required (non-defaults). c,d are optional (have defaults)

def func(a, b, c=1, d=1)

return a + b + c + d

return vs yield

- return is used to exit the function and return a value

- yield will suspend the execution of the function and return a value. the function can be resumed later by calling it again

generator is a function that returns an iterator. An iterator is an object that can be used to iterate over a sequence of values.

example of generator and yield

def my_generator():

for i in range(10):

yield str(i)

rules = [i for i in my_generator()]

results = list(rules)

print(results)

Calling the function

- func(1, 1) Called using two positional arguments. Default c,d will also be used but not shown

- func(1, 1, 1, 1) Called using four positionals, no keywords used (and no defaults used)

- func(1, 1, d=1, c=1) Called using positionals and keywords (keyword position doesn’t matter)

a and b can also be passed using keywords

- func(d=1, c=1, b=1, a=1) Called using keywords, order/position does not matter. c,d were still optional.

if 1 of the positionals is used (passed without keyword) the order is important. Positional (non-default) must be first.

- func(1, b=1) Called using one positional and one keyword, b.

- func(b=1, 1) Not allowed - SyntaxError: positional argument follows keyword argument

Positional is still required too. Argument ‘a’ is missing below

- func(b=1, c=1) Not allowed - missing 1 required positional argument: ‘a’

The * can be used to force an argument to be passed by keyword-only.

Any argument after * must be passed using a keyword.

def func(a, b, *, c=1, d=1):

a,b are still positional. c,d must now be passed using keywords

- func(1, 1, 1, 1) Using four positionals doesn’t work now. TypeError: takes 2 positional arguments but 4 were given

- func(1, 1, d=1, c=1) Called using positionals and keywords (keyword position doesn’t matter)

def func(a, *, b, c=1, d=1):

# code here

return output

a is now the only positional. b, c,d must now be passed using keywords (c,d have defaults)

- func(1, 1, c=1, d=1) Can not pass two positionals. TypeError: takes 1 positional argument but 2 positional arguments (and 2 keyword-only arguments) were given. Keywords could still be used for all four arguments though.

- func(d=1, c=1, b=1, a=1) Called using keywords, order/position does not matter. c,d were still optional.

With Python3.8 the / can also be used to force arguments to be called by position (using keyword is not allowed)

def func(a, /, b, *, c=1, d=1)

a is now positional-only. b is still positional but can use keyword, c,d must use keywords

- func(a=1, b=1, c=1, d=1) Will not work. a is positional-only. TypeError: got some positional-only arguments passed as keyword arguments: ‘a’

- func(1, b=1, c=1, d=1) is good.

Generator (ie. range(0,10,2))

- Will generate but not store to memory

- Can cast it to a list to save it to memory and print it

list(range(0,10,2))

List comprehension

Flattened for loop. Less code space than doing i = i + 1 or list.append in a loop.

sensor = [i for i in range(4)] --> [0, 1, 2, 3]

# 2-dimensional

sensor = [[x for x in range(1, 3)] for x in range(4)] -> [[1, 2], [1, 2], [1, 2], [1, 2]]

list = [x**2 for x in range(10)] -> [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]

even = [x for x in range(0,11) if x % 2 ==0] -> [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

tempC = [0, 20, 40, 80]

tempF = [(9/5*temp+32) for temp in tempC]

oddeven = [x if x%2==0 else 'ODD' for x in range(0,11)]

colors_list = [['blue', 'green', 'yellow'],

['black', 'purple', 'orange'],

['red', 'white', 'brown']

]

new_colors_list = [(y + '_color') for x in colors_list for y in x]

print(new_colors_list)

enumerate

Enumerate to include a counter. Will come back with tuple but can unpack

rpiPins = [10, 14, 15, 18]

for i, pins in enumerate(rpiPins):

print(f'index={i} and pin={pins}')

for i, pin in enumerate(pins, start = 1): (start is optional, otherwise starts at 0)

io_pin[i] = Pin(pin)

Unpack a tuple (tuple unpacking)

alist = [(1,2),(3,4)]

for a,b in alist:

print(a)

print(b)

Unpack a dictionary

if isinstance(varD, dict):

for key, value in varD.items():

print("{0}:{1}".format(key, value))

Unpack a nested dictionary

for parm, item in varD.items():

if isinstance(item, dict):

for key in item:

print("{0}, {1}, {2}".format(parm, key, item[key]))

* and ** Operators (*args, **kwargs)

The * will unpack any iterable object (strings, lists, tuples, dictionaries)

** will unpack dictionaries

Can be used as another method for combining lists

listA = [1, 2, 3]

listB = [4,5,6]

listC = [*listA, *listB]

print(listC) = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

print(*listC) = 1 2 3 4 5 6 (unpacked)

So * and ** can be used in passing arguments to functions (*args, **kwargs)

- *args used to pass non-keyworded variable length argument list

- **kwargs used to pass keyworded variable length argument list

def servos(*args):

print(*args) # will unpack and print 1 2 3 on one line

for arg in args: # will iterate thru args and print 1, 2, 3 on new lines

print(arg)

print(servos(1, 2, 3))

def motor(**kwargs):

for key, value in kwargs.items():

print ("do setup using key:{0} and value:{1}".format(key, value))

for arg in kwargs: # will only print the keys.. motorA motorB

print(arg)

for arg in kwargs.values(): # will print the values 1 2

print(arg)

motor(motorA=1, motorB=2)

kwarg used to combine two dictionaries

dict1 = {'hello':1, 'hello2':2}

dict2 = {'hello3':1, 'hello4':2}

dict = {**dict1, **dict2} # will combine the two dictionaries

print(dict)

Print formatting

Formatting (place holder %, format, and f-string)

Examples below are format and f string

print("motor was spinning {rpm:1.2f}".format(rpm=motor-speed))

rpm = motor-speed

print(f'motor was spinning {rpm:1.2f}')

Float formatting is {value:width.precision f}

voltage = 1.24543534

modulo = "%.2f"%voltage

format = "{:.2f}".format(voltage)

fstring = f"{voltage:.2f}"

# Note - formatted variable will be a string type

print(type(fstring))

To format a list of data

data = [1.23423, 423.2432, 1.2]

formatted_data = ["%.3f"%x for x in data]

formatted_data = ["{:.3f}".format(x) for x in data]

formatted_data = [f"{x:.3f}" for x in data]

map, filter, lambda

map will run a function on each item in a list,object

filter is similar but will return items that are true based on the function

You first give it the function and then the list,object

Will need to iterate through map()/filter() or cast it to a list

map example

def square(num):

return num**2

mylist = [1,2,3,4,5]

# iterate

for item in map(square, mylist):

print(item)

# cast to list

list(map(square, mylist))

filter example

def is_even(num):

return num % 2 == 0

mylist = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

list(filter(is_even,mylist))

lambda is an anonymous, adhoc, function (you don’t use ‘def’ and give it a name) meant to run once for a simple task. Useful for when you are using a function that requires a simple functin passed into it. You can use lambda instead of formally defining the function.

example of formal function

def square(x):

return x**2

Converted to lambda

remove the ‘def square’ name and put the return on the same line

lambda x: x ** 2

Could be used in the map/filter examples

instead of defining a ‘square’ function just use lambda

list(map(lambda x: x ** 2, mylist))

list(filter(lambda n: n % 2 == 0,mylist))

Inheritance (Child Class)

Create a class that inherits the functionality (properties and methods) from another class by passing the parent class as a parameter.

class halogen():

def __init__(self, pin):

self.pin = pin

self.type = "halogen"

def on(self):

print("light is on. pin= {} and light={}".format(self.pin, self.type))

class led(halogen):

def __init__(self, pin, socket):

self.pin = pin

self.type = "led"

self.socket = socket

toggle1 = led(4, 6)

toggle1.on()