Intro to cli terminal commands

For windows you can use cmd.exe or PowerShell. The Anaconda environment would not activate in PowerShell so I use cmd.exe (updated vscode in command palette. Terminal:Select default profile)

sudo, su, root

The following assumes you’re either a single user on a Linux distro or Raspberry Pi. By default there are two user names on RPi, “pi” and “root”. (For non RPi systems replace “pi” with your user name entered during install) “pi” is the default user and is a member of the sudo group. This means you can run commands as root using sudo and can switch to the root user with $ sudo su “root” is the superuser and has complete access.

- You can add more users which will create another “home” directory (pi is under /home/pi)

-

$ su <username>is used to switch between users; logout and login to another. (If no username is specified it will try to login to root but requires root password. See more below) -

$ whoamiat any point will show you the user currently logged in - sudoers file has configurations

When you need superuser/root it is best to use option 1 when possible. Options 2-4 can gain root by “sudo” and stays at that level (but without having to switch the user to root). Also ~/.bash_profile, .profile, .bashrc and /etc/profile will be executed. whoami=root. Only requires user password. Command line will have #. Type ‘exit’ to leave

-

$ sudo <command>RECOMMENDED. Temporarily elevate pi user to root privileges. You are still the pi user but have root privileges for one command. -

$ sudo -ipreferred root method due to cleaner interaction with environment variables. Will give you interactive root shell and change to root environment, pwd=/root. (sudo -s will not change environement) -

$ sudo su -Logs you into root with the root environment (pwd=/root) -

$ sudo suLogs you into root with the your environment (pwd=/home/pi)

If you try $ su - or $ su to log into root it will want root password, not user pswd. Disabled on debian (Pi)/ubuntu. (Set or change the root password by running sudo passwd root)

Note on ‘-‘ (or –login) indicates a login shell and will execute commands from the profiles /etc/profile ~/.bash_profile ~/.bash_login ~/.profile

when you see ‘#’ - needs to be executed with root privileges either directly as a root user or by use of sudo command

Ownership functions

Changing Ownership of a file

$ chown USER:GROUP FILE

so.. $ chown <new-user> <file-name>

$ chown <new-user>:<new-group> <file-name>

Change ownership recursively in a directory

$ chown -R <new-user>:<new-group> <directory>

Make a File Executable

Making a file executable (+x vs 755)

chmod +x adds the execute permission for all users to the existing permissions.

The + is telling it to add permissions to what it already has (relative). A - (minus) would remove it.

$ chmod +x file.py

while chmod 755 says over write all, current permissions with what I’m providing, 755. (absolute)

755 = full permissions for the owner and read and execute permission for others.

More details on 755

- 755 correspond to read/write-execute permissions on a file/dir

- read = r (4)

- write = w (2)

- execute = x (1)

- When added it is the total permissions

For owner/group/others (ugo) you can set seperate permissions (hence 755)

- Owner= read/write/execute = rwx = 4+2+1=7

- Group= read/execute = r-x = 4+0+1=5

- Other= read/execute = r-x = 4+0+1=5

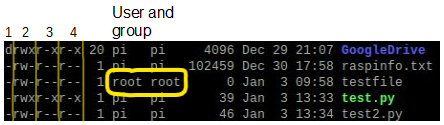

Example- When you do $ ls -lrt you see a list of files with details. (See screenshot above)

Columns

1: ‘-‘ = file. ‘d’ = directory

2: owner (u) permissions

3: group (g) permission

4: other (o) permission

(user and group ID are circled after that)

Note - using gedit for a file that needs sudo, root privilege (in GNOME)

gedit admin:///etc/default/grub

$PATH

The understanding of bin/executables and how your system knows where to look for these executables ($PATH) can be useful. $PATH is a system variable that defines what directories will be searched for executables. To see your $PATH setup.

$ echo $PATH | tr ":" "\n"

/usr/local/sbin

/usr/local/bin

/usr/sbin

/usr/bin

/sbin

/bin

As an example, take the executable ‘ls’ used to list contents of a directory. If you do $ which ls it will output /bin/ls. Meaning the ‘ls’ executable file is located in /bin/ dir, which is listed in $PATH above. So when you type $ ls your system knows from $PATH what directories it can search and it will find ‘ls’ in /bin. (If you go to the /bin/ dir and list the contents you will see many command utilities listed)

Creating your own simple shell/bash file in a dir, making it executable, and then adding that dir to your $PATH so you can execute it from any location can help understand the concept

(Example below will be assuming working on a RPi and the home dir = /home/pi (or you can use $HOME)

- Create a test dir

$ mkdir test- Create a test file (bash file)

$ touch hello- Add the shebang and echo line to ‘hello’ file to output some txt. (#!/usr/bin/env bash tells the system to use ‘bash’ to run your file)

$ nano hello#!/usr/bin/env bashecho hello- Now make the ‘hello’ bash file executable with

$ chmod +x hello- As long as you tell the system the location of your bash file you can execute it. For example if you’re in the ‘test’ dir you can run

$ ./hello- (the ‘.’ tells it is in the current, working dir) or if you go to another dir you could execute with

$ /home/pi/test/hello- But if you try and execute it without listing the location of the file (ie $ hello) you will get an error bash: hello: command not found. This is because the system * didn’t know where to look for your ‘hello’ executable file.

- However if we add the location of the ‘hello’ file (/home/pi/test/) to the $PATH variable it will know where to look and you can execute it without specifying the location.

- To add /home/pi/test/ to your $PATH type

$ export PATH=$PATH:/home/pi/test- Now you can type

$ hello- from any location or directory and it will execute.

- NOTE - once you close your terminal it will lose the $PATH update you made and not work anymore. To make it permanent you need to add the ‘export PATH=$PATH:/home/pi/test’ to one of your profiles that are loaded when you open a terminal. (ie .profile or .bashrc)

- From your home dir type

$ nano .bashrc- add

export PATH=$PATH:/home/pi/testto the bottom of the file and save it. - Now when you open a terminal and type

$ helloit will know to look for your executable ‘hello’ script inside /home/pi/test - To reload without having to logout/login use

source ~/.bashrcor. ~/.bashrc - To clean up go remove the line.

Setting Environment Variable You can test out creating your own environement variable

$ export TEST=hello$ echo $TEST

Again, once you close the session it will not exist. To make it persistent add it to a profile. Add Env Variable to Profile (.profile or .bashcrc)

- Example..

$ nano .bashrc- and add

export TEST=hello - Now save

PYTHONPATH

Python has a similar path setting that you can use -> PYTHONPATH It will be empty initially. You do not need to set it up, however it can be good practice to understand the PATH concepts. You can create your /bin/ dir where you store your executable python scripts and update the PYTHONPATH so you can run these scripts from any location (without having to specify the full path)

Example below will be assuming working on a RPi and the home dir = /home/pi (or you can use $HOME)

Create your own simple executable python file

- From your home dir create directories bin and lib/python

$ mkdir bin lib$ mkdir lib/python- Keep python executable scripts in /bin/

- Keep python libraries you create in /lib/python

- Go to the ~/bin/ dir and create a test python script

$ touch pyhello.py- Add the shebang and print line to ‘pyhello’ file to output some txt. (#!/usr/bin/env python3 tells the system to use Python3 to run your file)

-

$ nano pyhello.py#!/usr/bin/env python3 print("hello from py") - Now make the ‘pyhello.py’ script executable with

$ chmod +x pyhello.py- From your home dir type

$ nano .bashrc- and add these lines at the bottom

PYTHONPATH=$HOME/lib/python export PYTHONPATH - Now your own lib/python dir with your Python libraries will be added to your Python path. Reboot your system and your $HOME/bin will be added to your search path.

- Open a terminal and you can execute pyhello.py from any location.

-

$ pyhello.pyThe concept is you can now keep your executable python scripts in ~/bin folder and execute from any location.

regex,awk,sed,grep

Regular expression (regex), grep, sed, awk

Three common Linux commands for text processing are grep, sed, awk. Although there is some overlap each have a strength. The search pattern tool used with them is regular expression or regex.

regex

Regular expression is a type of search pattern used with the grep and sed. It allows complex search patterns (special characters are used). Can be used in commands, functions, programming, etc. For example used in Python with the “import re”. Note regex is different than filename “globbing” where ? and * are used as wildcards to find a filename. Link to regex101 testing site

- rep - give grep a text input and a “regular expression” and it will search line-by-line looking to match your regex. It will then output every line a match was found.

- sed - does substituion. give sed a pattern to match and what you want to replace it with.

- awk - acts as an ad-hoc table or database; separating fields. You can specify which field to output.

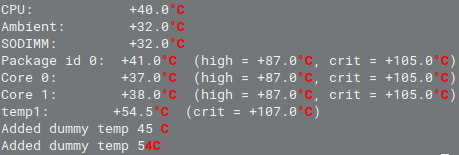

To become familiar with the tools it is best to get a text file you want to parse and experiment with the commands. There are many applications (text, log files) but I’ll focus on a sensor report from my PC. This is a common use in conky system monitors.

Quick setup guide for lm-sensors. More details at Ubuntu. First install

$ sudo apt install lm-sensors- You need to load sensor modules.

$ sudo sensors-detect- can edit /etc/sensors.conf

- See sensors.conf for details

$ man sensors.conf

You can have the script insert sensor modules into /etc/modules or edit /etc/modules and add what you want. May need to run $ service kmod start

$ sensors > sensors.log

Dell

Adapter: Virtual device

Processor Fan: 2684 RPM

CPU: +40.0°C

Ambient: +32.0°C

SODIMM: +32.0°C

BAT0-acpi-0

Adapter: ACPI interface

in0: 12.47 V

curr1: 1000.00 uA

coretemp-isa-0000

Adapter: ISA adapter

Package id 0: +41.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

Core 0: +37.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

Core 1: +38.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

acpitz-acpi-0

Adapter: ACPI interface

temp1: +54.5°C (crit = +107.0°C)

grep

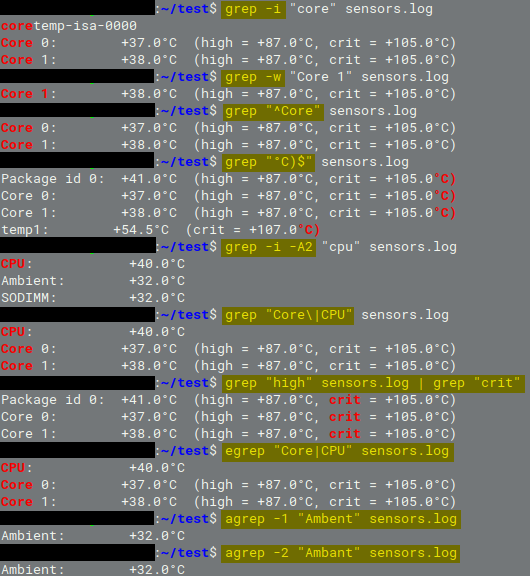

Quick grep example on the sensor.log to find “Core”

(see “More about grep” below for details)

$ grep "Core" sensors.log

Core 0: +37.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

Core 1: +38.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

Details on grep, egrep, agrep There are many grep options. Here are a few common tools for matching text in a file

Don’t forget $ man grep and $ info grep

Important note on meta-characters.

grep - ‘?’, ‘+’, ‘{’, ‘|’, ‘(’, and ‘)’ lose their special meaning. You need to use blackslashed versions ‘\?’, ‘\+’, ‘\{’, ‘\|’, ‘\(’, and ‘\)’. See gnu.org So OR is \|

egrep - (extended grep) you do not have to backslash. OR is simply | . This makes some expressions easier to view. (examples below)

agrep - does approximate matching. You specifiy how much error with -1, -2. (example below)

Basic syntax

$ grep [options] pattern [file]-

$ grep -n "Core" sensors.logPrint line numbers where “Core” is found in sensors.log

More options

- -i (not case sensitivie)

- -w (match the exact word)

- -v (inverse, show lines without that string)

- -n display the line number the match was found

Returns matching line plus a number of lines before(B), after(A), or both (C) - -B 1

- -A 1

- -C 1

Pattern expressions

- . = match any single character, but must be a character/space there

- ? = preceding item is optional and will be matched at most once

- + = match preceding character one or more times, but must appear once.

-

- = match preceding character zero, one, more times, but must have a preceding character

Play with the * , It’s different than globbing.

- = match preceding character zero, one, more times, but must have a preceding character

-

$ grep * filewill have no match (no preceding character to match) -

$ grep .* file(and$ grep "a*", etc) will match every line - ^abc starts with “abc”

- abc$ ends with “abc”

- (Brackets expressions continue below)

Examples ran on the sensors.log file. Note “egrep” and “agrep” used at the end.

egrep used to include multiple words without having to escape the |.

agrep has ability to match approximate words (you specify how much error to allow)

Example Ambient

$ agrep -1 "Ambent" sensors.log

-1 = one error

$ agrep -2 "Ambant" sensors.log

-2 = two errors

More egrep

To match all the 1’s

$ grep '1' sensors.log

If I want to include the 1’s that have a + then use the ?=optional on preceding character

$ grep '+\?1' sensors.log

or I can use egrep and not have to backslash the ?

$ egrep '+?1' sensors.log

Brackets - any character in the bracket can be used for matching at that position

$ grep 't[ow]o' file will find “too” and “two”

To find various methods of temp (ie 32°C or 32C or 32 C)

Search for any number, space or ° before a “C”

$ grep '[0-9° ]C' sensors.log

Can use it to find a range of numbers

Find any lines with “crit” and then 101. to 106.

$ grep 'crit.*10[1-6]\.' sensors.log

Package id 0: +41.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

Core 0: +37.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

Core 1: +38.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

To find any line with an opening and closing parenthesis ()

$ grep '(.*)' sensors.log

To find any line with () but only letters and single space inside, no numbers

Note there is a space after the “z”

$ grep '([A-Za-z ]*)' sensors.log

To find only lines that start with a Capital letter (headings) can use either

$ grep '^[A-Z]' sensors.log

$ grep '^[[:upper:]]' sensors.log

awk

awk breaks each line into field, based on spaces (default).

The whole line is $0, each field is $1, $2, $3 etc.

awk [options] script FILE

Field 1 2 3 ….

Core 0: +37.0°C (high = +87.0°C, crit = +105.0°C)

So pipe the output of grep to awk and get field 3, the temp.

$ grep 'Core 0' sensors.log | awk '{print $3}'

$3 is the temperature

+37.0°C

Now use cut to get rid of the “+” sign. Cut from 2nd to 8th char

$ cat sensors.log | grep 'Core 0' | awk '{print $3}' | cut -c2-7

37.0°

awk is a full programming language with loops, etc. It’s useful because it breaks each line into fields. The whole line is $0, each field is $1, $2, $3 etc.

awk [options] script FILE

Can print multiple columns

$ awk '{print $1, $2}' sensors.log Default for delimiter is space. Use -F to change it to comma delimited

$ awk -F "," '{print $1, $2}' sensors.log

To count how many “Cores” we have

$ awk '{count[$1]++} END {print count["Core"]}' sensors.log

Find column 3 (Core temps) greater than 37.5 and then print the row $0

$ awk '{ if ($3 > 37.5 ) {print $0} }' sensors.log

sed

sed can be used to substitute characters. This is useful for harmonizing documents, removing unwanted characters, spaces, etc.

$ man sed and $ info sed

$ sed [options] script FILE

-n (do not print lines)

-i (edit in place)

Run the command to see what would happen (it won’t change the file)

Then add “-i” and run the command to update it

(or “-iBU” to create a new file with “BU” at the end)

g (at the end means global across the entire text)

-r (use egrep or extended grep)

Note - the delimiter does not have to be /. The first character after “s” is the delimiter. So the delimiter can be a space, underscore, comma, etc. This is useful to make scripts simpler to read depending on your string.

Can change “RPM” to “rpm”

$ sed -i 's/RPM/rpm/' sensors.log

Remove the “+” in front of the temps

$ sed -i 's/+//' sensors.log

Create a backup when running

$ sed -niBU 's/RPM/rpm/' sensors.log

Replace dell and Dell with HP

$ sed 's/[dD]ell/HP/' sensors.log

Can specify a line or range of lines to limit the replacement to

$ sed '1,3 s/[dD]ell/HP/' sensors.log

Replacing a space / / with nothing //. The g tells it globally across the entire text.

$ sed 's/ //g'

Replace multiple spaces with []

$ sed 's/[ ]/ /g'

or $ sed 's/[ ]\+/ /g'

Example with file “html”

$ cat html

<td>data1</td>

<td>data2</td>

<td>data3</td>

To remove spaces

$ sed -i 's/[ ]/ /g' html

To remove the td and /td. Make it easier to view by changing delimiter to _ and use -r for extended regexp (egrep). Now you don’t have to escape the ? to indicate the preceding / is optional. Both td and /td will match

$ sed -ri 's_</?td>__g' html

$ cat html

data1

data2

data3

the regex version would be

$ sed -i 's_</\?td>__g' html

Helpful Terminal Commands

When you run a command like ‘ls’, ‘cd’, ‘cp’, etc you are calling a binary/executable file to perform some function (list contents, change directory, copy a file, etc). Similar to if you created a shell/python script and made it executable from any location (see Advanced section below for more on that)

Magpi has a good article on command lines but below are some quick ones..

Two very helpful command line cheats As you start typing a dir/file you can hit the tab button and it will auto-complete (as far as it is unique). Hit tab twice quickly to see matches. The terminal keeps a history of commands you typed. Just hit up/down arrow to scroll thru them.

Most important command if you’re new to the terminal is “man”. An interface to the on-line reference manuals.

-

man <command>

To show pages the command is on man -f <command>-

man -f daemon

daemon (7) - Writing and packaging system daemons

daemon (3) - run in the background

Then to view that page man 7 daemon

Commands to frequently run and keep your system up-to-date

-

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -y

(or full-upgrade which will remove packages if needed to update the whole system. Confirm which packages will be removed) -

sudo apt-get install -f(fix partial upgrades) -

sudo killall apt apt-get(kill all running process) date-

calDir/File commands

Directories/Files

-

pwdDisplay the path for the directory you are in (current working dir) -

cd <directory>Change directory -

cd ~Change to home directory -

lsList contents of directory -

ls -lrt(-lrt will list long, detailed, by creation time in reverse order)

Can use * and ? wildcards, globbing. -

ls -l *text* *text*glob pattern will return all files/directories with ‘text’ in the name.

Can use ? wildcard to indicate wild for a single character. -

ls -l *.??Would return all files with a 2 letter extension. -

ls -laSee hidden files use -a (hidden files start with ‘.’) -

ls -l .*text*See hidden files with name ‘txt’ in them -

ls -lrt | moreIf there are a lot of files can page through them (seeor pipe usage further down)

(you may have to use sudo depending on the directories you are working with)

-

mkdir <directory>Create a directory -

mkdir -p <directory>If dir already exists will create child directory inside it -

touch <file>Create a file -

rm <file>Delete file -

rm -r <directory/>Delete directory and its contents (-r is recursive) -

rm -rf <directory/>Remove directory recursively and forcibly -

mv <old file> <new file>Change name of a file -

mv <file> <destination directory>Move a file -

cp <file> <destination directory>Copy a file -

cat <file>Display contents of a file -

less <file>Display contents by page

Pipe/grep

Using Pipe | and grep for Advanced Text Searches

grep is used to search for a text match in the contents of files (using regular expression). There are many grep options but here are a few common tools for matching text in a file.

Don’t forget man grep and $ info grep

Basic syntax

grep [options] pattern [file]

Some options

-r (Recursive. Search inside directories, too)

-i (Not case sensitive)

-w (Match the exact word)

-v (Inverse, show lines without that string)

-n (Display the line number the match was found)

Returns matching line plus a number of lines before(B), after(A), or both (C)

-B1

-A1

-C1

Pattern expressions

. = match any single character, but must be a character/space there.

? = preceding item is optional and will be matched at most once

+ = match preceding character one or more times, but must appear once.

* = match preceding char zero or more times, but must have a preceding char.

Play with the * and ? in a test file (It’s different than globbing)

- ```grep * file will have no match (no preceding character to match)

-

grep .* file(and$ grep "a*", etc) will match every line

^abc starts with “abc”

abc$ ends with “abc”

Important note on meta-characters.

grep - ‘?’, ‘+’, ‘{’, ‘|’, ‘(’, and ‘)’ lose their special meaning. You need to use blackslashed versions ‘\?’, ‘\+’, ‘\{’, ‘\|’, ‘\(’, and ‘\)’. See gnu.org So OR is \|

egrep - (extended grep) you do not have to backslash. OR is simply | . This makes some expressions easier to view.

agrep - does approximate matching. You specifiy how much error with -1, -2. (example below)

Using egrep to search for mulitple items (|=OR, &=AND)

egrep 'apple|orange|pear'

Brackets - any character in the bracket can be used for matching at that position

-

grep 't[ow]o' "file" will find "too" and "two"

ie to find various methods of temp (ie 32°C or 32C or 32 C)

Search for any number, space or ° before a “C”

*grep '[0-9° ]C' "file"

To find all variables named “self..something..File”

-

grep -i "self.*file" *

To only find variables with three character and then “File”

To find any line with an opening and closing parenthesis () in all (*) files.

-

grep '(.*)' *

To find any line with () but only letters and single space inside, no numbers

Note there is a space after the “z” -

grep '([A-Za-z ]*)' "file"

To find only lines that start with a Capital letter (headings) can use either -

grep '^[A-Z]' "file"or grep '^[[:upper:]]' "file"

A good grep habit is to put text inside “ “ quotation marks

-

grep "text" <file>Search for “text” match in(current directory). -

grep -rl "text" /pathSearch for “text” match at /path and recursively (-r) inside its directories. -

grep -r "text" *Search for “text” match inside all files and output the files plus occurrence -

grep "text" * > resultsSearch for “text” match inside all files and send results to file “results”

Combine pipe | with grep for more options. The pipe | sends output of one command to another.

-

<cm1> | <cmd2>(Send the output of cmd1 to cmd2) -

echo $PATH | grep "sbin"Output contents of $PATH to grep and highlight ‘sbin’.

Useful way to output variables -

echo $PATH | tr ":" "\n"(use the ‘tr’ to replace a character with return line \n. This puts each value on a new line making it easier to view.) -

ls -la ~/ | moreSee hidden files by page

Search for a Specific File or Directory and Compare

Useful commands for locating files are “find” and “locate”.

find - can use regex as an option or pipe to grep and use regex. But results are slightly different. Create a set of test files with different extensions and test out your searches to get comfortable with it.

Don’t forget $ man find for more details

Basic syntax

-

find /dir -name "filename"

-name (find a file by its name)

-iname (not case sensitive)

-L (follow symbolic links)

-type (f=file, d=directory, l=symbolic link)

Find/mlocate

Find using wildcard/globbing

Can use * wildcards, will only find files.

Quotes are important for recursive search

-

find . -name "file*"(start search in current directory) -

find / -iname "file*"(start search in root directory) -

find $HOME -iname "*file*.dat"(start search in home directory) -

find / -name "*.txt"Find all files with specific extension

find using regex option

find . -regex "expression"

find using pipe to grep

-

find . -print | grep -i "file"Pipe it to grep and use regular expression. Do not need to use * wildcards, will find files and folders. -i means case-insensitive

see grep page for more regular expression options

If you don’t know the exact name try “agrep”

-

sudo find . -print | agrep -1 "fle"The -1 looks for match within one error, can do -2, etc.

Example directory with following files

sensors.log

sensors.txt

sensors.log2

dummy

Use find, find/regex, find/grep

-

find . -name "*sensor*log"

./sensors.log -

find . -regex ".*sensor.*log"

./sensors.log -

find . -print | grep ".*sensor.*log"

./sensor.log2

./sensors.log

mlocate (or locate) keeps a database of path names. Returns all results starting at root.

man mlocate-

sudo updatedb(update the database of path names) mlocate "file"-

mlocate -b "\filename"(must exactly match file) -

mlocate --regex "file"(use regular expression) -

mlocate --regex ".*flatpak.png"(file flatpak.png icon)

For visual tree

tree -P "*file"-

tree -Pa "*file"Include hidden files

grep options useful if searching for files

-r (recursive)

-H (list filename)

-

wc -ldummy.txt Number of lines in the file (-w for words, -m for count of characters) ls / | wc -lls . | wc -l

To compare two files side by side

-

diff -y <file1> <file2>

(gui versions you can install are Kompare, Meld, Diffuse)

Search for Programs, Apps, Executables

For program version

<programname> -V<programname> --version

See if a program is running

-

ps aux | grep <program name>

See all programs running -

ps -A

Can kill a program with kill -9 <PID> or $ kill -kill <PID>-

killall <name> (kill by program name)or -

pkill <program>

more details with ps aux

To start a job in the background use &

-

program &

(ie $ mpg321 file.mp3 &)

To see jobs running -

jobs

Then to kill it kill %1

Find program type and location

which will return the path name of the program that would be executed if found in $PATH

-

which <programname>

To show all matching executables use -a -

which -a <programname>

whereis attempts to locate the desired program in the standard Linux places, and in the places specified by $PATH and $MANPATH. It is used to find binary, source, and man pages. -

whereis <programname>

options -b (binary) -s (source) -m (man pages) -

whereis -b <programname>

Output Command, Environment Variables to Text

The > sends output of a command to a file -

<command> > <file>Output command result to file

example $ echo $PATH > test will output the contents of $PATH to ‘test’ file -

<command> >> <file>Append the output of command to file

Environment Variables

-

envTo see list of variables -

echo $PATHTo output variable value

globbing

globbing vs regular expression

When researching wildcard/matching you may come across the terms globbing and regular expression (regex)

Globbing filenames is a simpler method of using * and ? wild cards

* = match 0 or more characters

? = match a single character

Regex is used in commands for pattern matching in text and has more complex options. A good tutorial to learn how it works is regexone

Running Command with sudo/root

Running commands from root (see sudo section for more details)

Most common, temporary method, is

-

sudo <command>

To stay as root run

sudo -iorsudo su -orsudo -s

(su is used to change users)

To run previous command with sudo -

sudo !!

Get Operating System and Hardware Info (lsb_release)

Couple quick options to see what operating system release you’re running (helpful when installing programs) lscpulsb_release -a-

lsb_release -cs(code name) cat /etc/os-release-

cat /proc/cpuinfo uname -a

More detailed info on RPi sudo apt install raspinforaspinfosudo apt-get install lshwsudo lshw

Another option that gives a summary is neofetch or screenfetch

sudo apt install neofetch To install-

neofetch To get details on system

(for screenfetch, same commands, just replace with screenfetch)

DE = Desktop Environment

WM = Windows Manager

Disk Usage

df -h

Images can you col-# col-sm-# col-md-# col-lg-# Use auto to auto size around image Just wrap your images with <div class="col-sm"> and place them inside <div class="row"> (read more about the Bootstrap Grid system).